The Fitzwilliam Museum and the Museum of Classical Archaeology in the Classics Faculty are jointly hosting an exhibition called Codebreakers and Groundbreakers.

The Fitz’s exhibition focusses on the decipherment of Linear B (by the architect Michael Ventris aided by John Chadwick, then a newly appointed lecurer in Classics at Cambridge), and, a little earlier, the cracking of German codes during the Second World War at Bletchley Park by Alan Turing and others.

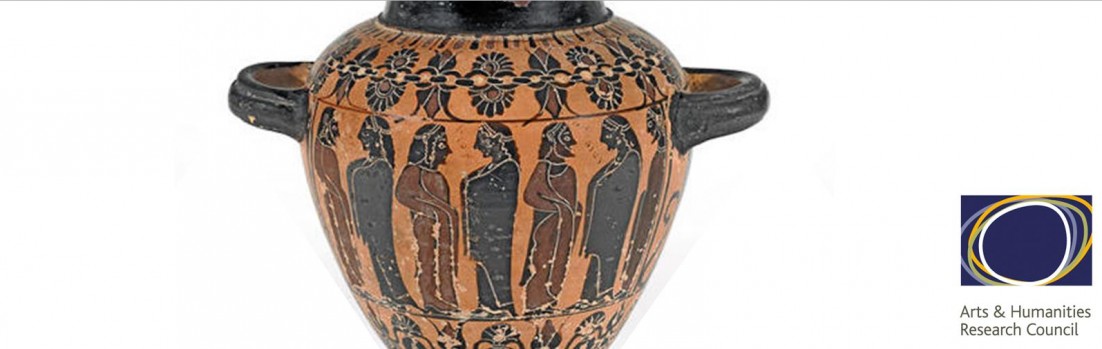

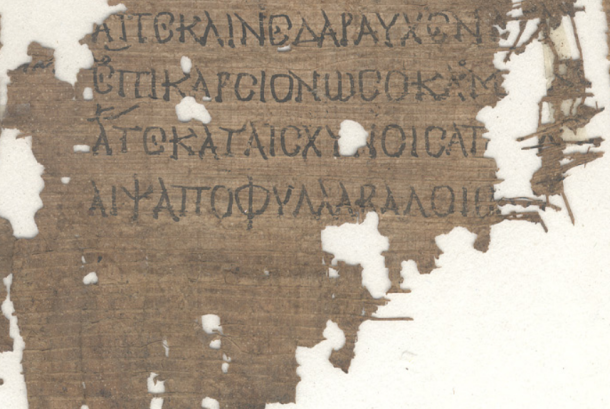

The Classics Faculty includes items from the archive of Alan Wace, who was the archaeologist who excavated Mycenae and discovered tablets written in Linear B, and features displays by current Faculty projects which rely on both ‘codebreaking’ and ‘groundbreaking’: the CREWS (Contexts of and Relations beween Early Scripts) project, the Greek Lexicon, the Myceneaen Epigraphy Group, and us at Greek in Italy!

Above you can see our panel at the exhibition. We think it’s pretty cool, and recommend that you go and see it and the rest of the exhibition in both venues (it’s on until the 3rd February, so there’s still plenty of time).

Thanks to Francesca Bellei, who designed the panel and wrote the text!