The Latin word for ‘bilingual’ is bi–linguis –e. As a formation, it “literally” means ‘having two tongues’, just as the poet Ennius said that he had three hearts (tria cordia) because he knew how to speak Greek, Oscan, and Latin (Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights XVII 17.1). The adjective bilinguis is one of a sizeable set of compounds that begin with bi– (see OLD, pp. 232-235).

The formal equivalent of bilinguis in Greek is δί-γλωσσος (again, “literally”, ‘having two tongues’, a neat illustration of how stems used in compounds can have the force of a singular or plural or dual). Whence come διγλωσσία and English ‘diglossia’ (‘being bilingual in your own language’, as I was taught) and ‘diglot’, a technical term for a book like a Loeb.

Both bilinguis and δίγλωσσος are not just formal equivalents; they also have the same range of meanings, connotations, and applications.

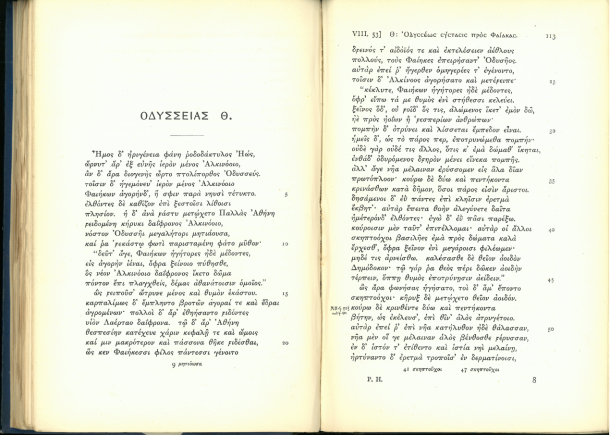

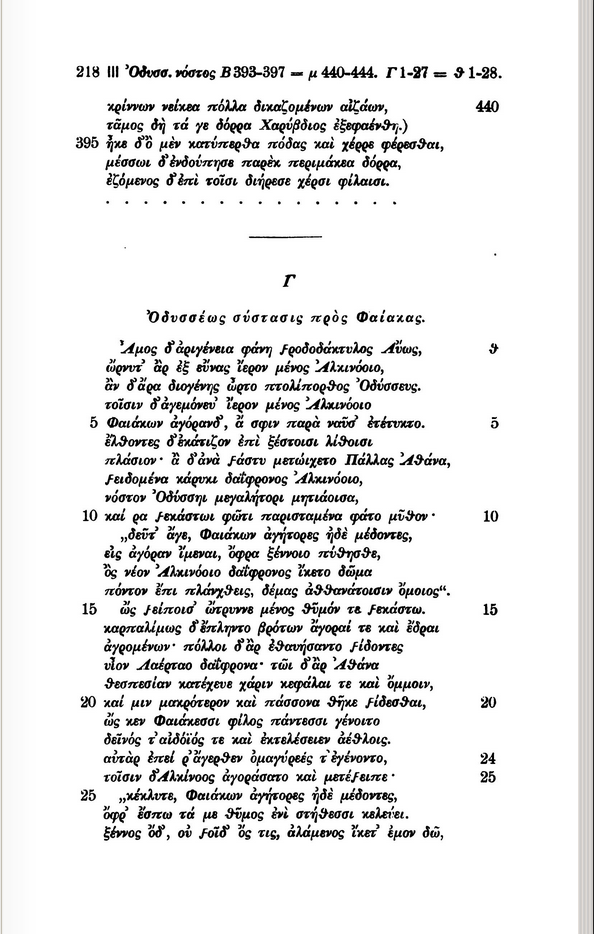

OLD lists the adjective as a description of ‘things’ with two tongues, of people with two languages, and of people who are ‘double-tongued, deceitful, treacherous’. LSJ has ‘speaking two languages’ for Thucydides and Galen (in his famous discussion of the nature of Koine Greek), but also ‘interpreter, dragoman’ in Plutarch. LSJ then continues ‘double-tongued, deceitful, LXXSi.5.9, al.’ (As ever, there is a question of what ‘al.’ means: officially ‘elsewhere in the same author’. This meaning occurs elsewhere in the LXX and in Siracides at that, but also in other authors, as DGE s.v. II 2 reports. ‘etc.’ would have been appropriate this time.) From DGE, we can add a double-tongued singing cicada (Anth. IX 273.2). Since γλώσσα can be anything tongue-shaped (LSJ s.v. III), doubtless, various objects could be ‘double-tongued’.

The Persian by Plautus has one character describing another as tamquam proserpens bestia est bilinguis et scelestus (‘Like a snake he is evil and has a two-forked tongue’: line 299). Virgil, Aeneid I 661, might be better known: domum timet ambiguam Tyriosque bilinguis (‘she fears the uncertain house and the “bilingual” Tyrians’).

The historian Quintus Curtius Rufus describes the Branchidae as:

mores patrii nondum exoleverant, sed iam bilingues erant, paulatim a domestico externo sermone degeneres.

They had not ceased to follow the customs of their native land, but they were already bilingual, having gradually degenerated from their original language through the influence of a foreign tongue.

History of Alexander the Great VII 5.29

This we would describe as ‘progress’ towards ‘language death’, in the context of language contact and cultural contact. However, we would do so more charitably than Curtius, who labelled the Branchidae as bilingual degeneres. That said, the Branchidae had sided with Xerxes and, to please him, had destroyed the Didymeon sanctuary (VII 5.28). Xerxes had resettled them. In VII 5.33-35, Curtius is more sympathetic to them as victims of genocide (or more hostile to Alexander).

In some instances, it is clear that treachery (1), not bilingualism (2), is in view, but the two go together in the case of the Branchidae and, more generally, as Rachel Mairs has discussed in ‘Translator, Traditor: The Interpreter as Traitor in Classical Tradition’, Greece and Rome 58.1 (2011), 64-81.

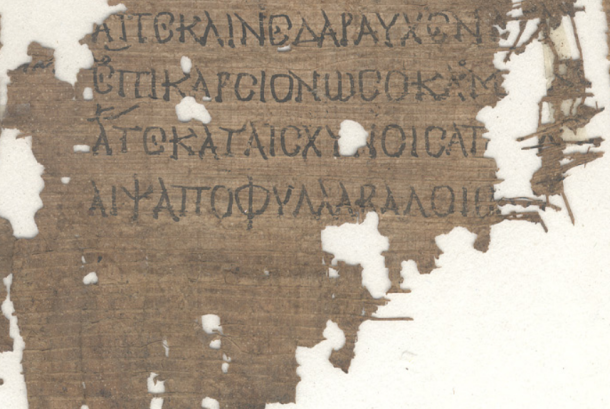

For (1), consider Didache 2.4, an early Christian text only rediscovered in 1883, and its parallel in the longer-known Epistle of Barnabas 19.7a:

οὐκ ἔσῃ διγνώμων οὐδὲ δίγλωσσος· παγὶς γὰρ θανάτου ἡ διγλωσσία.

You will not be double-minded, nor double-tongued: diglossia, you see, is the snare of death.

For (2), there are, among many other instances, bilingual Carian cities in Diodorus Siculus XI 60.4 (Greek cities with Persian garrisons) and an interpreter in XVII 68.5:

ἐν δὲ τούτοις ἧκεν ἀναγόμενος ἀνὴρ δίγλωττος, εἰδὼς <τὴν μὲν Ἑλληνικὴν καὶ> τὴν Περσικὴν διάλεκτον· οὗτος δὲ ἑαυτὸν ἀπεφαίνετο Λύκιον μὲν εἶναι τὸ γένος, αἰχμάλωτον δὲ γενόμενον ποιμαίνειν κατὰ τὴν ὑποκειμένην ὀρεινὴν ἔτη πλείω· δι’ ἣν αἰτίαν ἔμπειρον γενέσθαι τῆς χώρας καὶ δύνασθαι τὴν δύναμιν ἀγαγεῖν διὰ τῆς καταδένδρου καὶκατόπιν ποιῆσαι τῶν τηρούντων τὰς παρόδους.

Among these came hopefully a man who was bilingual, knowing *<the Greek and> the Persian language. He said that he was a Lycian, had been brought there as a captive, and had pastured goats in these mountains for a number of years. He had come to know the country well and could lead a force of men over a path concealed by bushes and bring them to the rear of the Persians guarding the pass.

* an example of a saut du même au même, an omission caused by skipping from the first occurrence of a word (τὴν ‘the’) to a second occurrence.

The words ‘he said that he was a Lycian’ sound a note of suspicion of (1) here… but, in this instance, that was in Alexander’s favour.

What has all this got to do with Greek in Italy?

Well, apart from the Greek historian Diodorus the Sicilian and then Galen, who was active at Rome in the second half of the third century (at the Imperial Court no less), it is enticing to speculate that the Latin bi– compounds have been influenced, to some extent, by their Greek formal counterparts. It is possible that biurus involves Greek οὐρά ‘tail’. If so, the name that Pliny the Elder reports Cicero as reporting for animalia…, qui uites in Campania erodebant (‘animals…, who would gnaw the vines in Campania’) would be a hybrid Latin-Greek compound. Two other bi– compounds, bilycnis ‘twin-lamped’ and bisyllabus ‘disyllabic‘, involve words that were Greek in origin (λύχνος and συλλαβή), but had their own currency as Latin words (lychnus and syllaba).

Neither the Didache nor the Epistle of Barnabas have any known connection with Italy, unlike other Greek texts among the so-called Apostolic Fathers (Ignatius wrote to the church in Rome, the letter known as 1 Clement was sent from the church in Rome to the church in Corinth, and the Shepherd of Hermas reports events in Rome and may refer to Cumae at 1.3 and 5.1, as Dindorf conjectured [although the Greek manuscripts have εἰς κώμας ‘into the villages’, one Latin version has apud ciuitatem Ostiorum and apud regionem Cumanorum respectively]). However, Codex Claromontanus (6th c. AD), which contains the letters of St Paul in Greek and Latin and which is thought to have been copied in Sardinia, contains a stichometric list that includes both the Epistle of Barnabas and the Shepherd of Hermas. Two of the leaves of this codex are palimpsest with the Phaethon of Euripides as their undertext (plates I-IV in J. Diggle’s Euripides: Phaethon [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970]). So, there are various other Greek in Italy connections.

More than that, there is the occasion for this post: editorial work has begun on Migration, Mobility, and Language Contact, Greek in Italy’s volume arising from the 2016 Laurence Seminar of the same name. This volume will include a chapter on interpreters by Rachel Mairs.