Last week was our second “Greek in Italy” project trip to the south of Italy. Like our last trip in September 2014, I’m sure that pictures and thoughts from this trip will keep bubbling up in my blog posts and articles for quite some time. But even though we’ve only just got back and I’ve not had time to go through all my notes and photos yet, I wanted to write a quick summary of what we did – partly to show off some great sites and museums which deserve more visitors, and partly to help remind myself later.

We started out in Paestum, which boasts some of Italy’s most beautiful and well-preserved Greek temples, dating from the sixth and fifth centuries BC. Today it’s a popular tourist sight, and rightly so. The temples are (mostly) not reconstructed – their amazing state of preservation made them a key sight of the Grand Tour. There are even some Early Modern engravings showing the temples all overgrown and disused.

There were plenty of inscriptions around the site to keep us busy, mostly in Latin. Inscriptions in Greek, Oscan and Latin have been discovered at Paestum, making it a very important site for research on ancient multilingualism in Campania and Lucania. We don’t know exactly which ancient region Paestum would have been in, since ancient authors aren’t always specific about borders: Paestum is in modern Campania, but is often considered to be part of ancient Lucania because of the use of Oscan in the Greek alphabet there.

Next we traveled to Velia, also known in Greek as Elea, home of several famous pre-Socratic Greek philosophers, the Eleatics. One of the main attractions of the site for me was the view, which naturally made me feel very philosophical. We made sure to take some time to ponder whether change is impossible (as believed by Parmenides) and a couple of Zeno’s paradoxes on the way up the hill.

Next we travelled to Roccagloriosa – a non-Greek site whose original Oscan name isn’t recorded in any ancient source. It’s near the later Roman colony of Buxentum, but distinct from it. Again, the views were brilliant – I think the whole team was in agreement that Basilicata (ancient Lucania) has some of the best landscapes in Italy. You can just about see the sea to the right-hand side of the picture below – I’d never realised that the sea would be visible from Roccagloriosa at all, despite having read about it for several years.

Roccagloriosa is a fascinating site, and despite its relative obscurity two important Oscan inscriptions have been found there. The longer text is a fragment of a bronze law, one of the earliest legal texts in Italy. Nick and I have written an article on this text, so it was great to see it in person again.

Excavators also found a piece of lead which bears both a commercial text in Greek (probably some kind of receipt) and a curse in Oscan. The photo below is a close-up in which you can just about see the small letters scratched on the lead.

The next day, we returned to Paestum to visit the museum. This silver disc with an obscure inscription in the Achaean alphabet attracted our attention. Even though it’s very clear indeed, it’s still not well understood. We’re not even sure what a couple of the letters are supposed to be (any suggestions for the letter on the left which looks like a tau with two legs?).

Of course we also had to visit Paestum’s fantastic tomb paintings. In general art history seems to prefer the paintings from the “Greek” era of the town, but we also have a fondness for the later “Lucanian” paintings. Most of these show gladiators stabbing each other, but there are also some evocative scenes of funerals and the afterlife, including a demon welcoming a woman’s soul into a boat to the underworld.

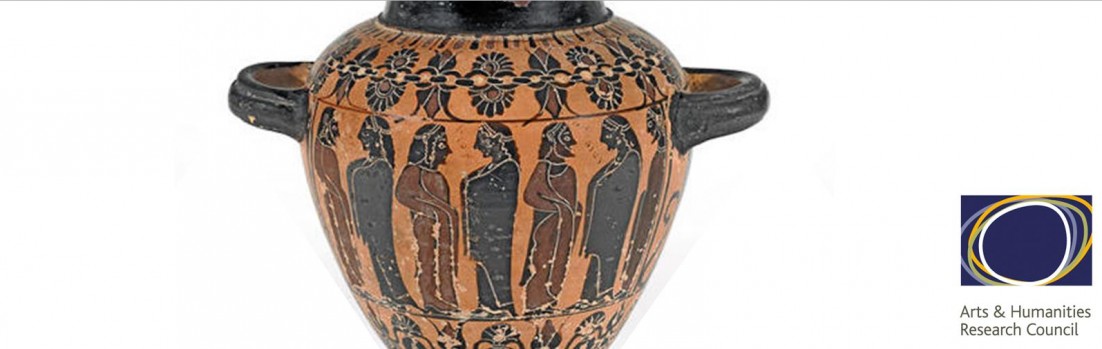

We then travelled to Metaponto, where we found this great early example of the Achaean Greek alphabet. By the time we got to Metaponto it was 41 degrees, and even the Italians were wilting a little.

Moving on to Puglia the next day, we travelled to Brindisi. Ancient Brundisium was at the very end of the Appian Way, the main road south from Rome. This is the column which marked the end of the ancient road. I’ve seen quite a bit of the Appian way this year in Rome and Capua, so it was great to feel like I’d finally completed that journey.

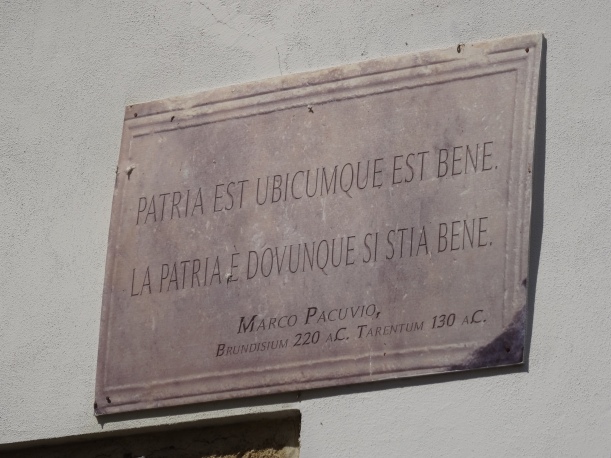

Brindisi has an extensive epigraphic collection in its museum, which kept us busy looking at many interesting borrowings and contact effects between Greek and Latin. Brindisi also takes its strong Classical heritage pretty seriously, since many early Latin authors including Pacuvius, Ennius and Livius Andronicus were from Brundisium, Tarentum and the surrounding area. Though the Ennius quote they’ve displayed was perhaps not the most exciting one they could have found.

On the Thursday, we went to the Grotta della Poesia in Roca, near Otranto, where we were shown around by Dott.ssa Mazzotta of the University of Salento. This was not only a beautiful beach resort, but also an incredible source of Messapic, Greek and Latin inscriptions, all hidden away in a huge cave. Before we arrived, we had no idea just how many inscriptions there were – but it turned out that the entire cave is covered in writing, which often overlaps and covers previous generations’ messages. We’d like to thank the British School at Rome for helping us set up this visit.

Since we were in the area, we also swung by the town of Calimera (Greek for “good morning”), which is one of the few towns in Italy where Greek is still spoken, in the form of the dialect Griko. We were rewarded by several signs and posters written partly in Griko, which our resident Greek speaker had a go at translating for us.

On our final day, we visited Canosa and Venosa on our way back to Naples. Canosa has a very interesting Daunian history, which we all know relatively little about, as well as some evidence of a Greek presense there. I was quite taken with this dice marked with the first six Greek letters instead of numbers or dots (note the digamma on the left hand side for the sixth letter).

Venosa was a Roman colony, called Venusia, but the museum there also includes some Oscan and Latin material from the nearby town of Bantia. This block is part of a dedication to Jupiter, written in Oscan in the Latin alphabet.

Before we flew back to the UK at the end of the week, we also went round the touristy but very fun Naples Underground tour, where we saw remains of Greek and Roman cisterns, and the flats and hotels built into the ancient theatre – highly recommended if you’re visiting Naples. We also visited the Roman street preserved underneath the Chiesa di San Lorenzo nearby.

And so what did all that look like? Something like this:

It’s been a very valuable trip for me – there’s nothing quite like putting the inscriptions and literature I’m working on in their context, and getting to see the landscapes and towns where this writing was produced. I feel very lucky to have taken not one but two trips to southern Italy with this project. Here’s one last photo of the team at the Grotta della Poesia, looking hot but pleased with our discoveries.