‘Greek in Italy’ should not be understood to mean that there was (ever) an ethnically- and dialectally-homogenous Greek population in Italy. As shown in the map below (from Wikipedia, s.v. Magna Graecia: map caveats duly noted), there were Doric, Ionic, Northwest Greek, and ‘Achaean’ coastal ‘pockets’.

The concern of this post is how we can associate with a particular dialect group a specific Greek individual that we can identify in Italy. One answer is features of that person’s name. Since the whole point is that people travel, it is not enough to say that since a name happens to be well-attested in a particular region, that particular name belongs to the dialect of that region. Put differently, I am not a car because I stand in a garage; or, just because I am named Patrick, it doesn’t mean I’m Irish.

While tracking down a paper about Egyptian loanwords in Greek, I found a fascinating piece by A.S. McDevitt entitled ‘A Thessalian in Magna Graecia’ (Glotta 46.3/4 [1968]: 254-256), about a Greek inscription in Achaean script on a bronze tablet found at Francavilla Marittima and dated to the middle of the 6th c. BCE.

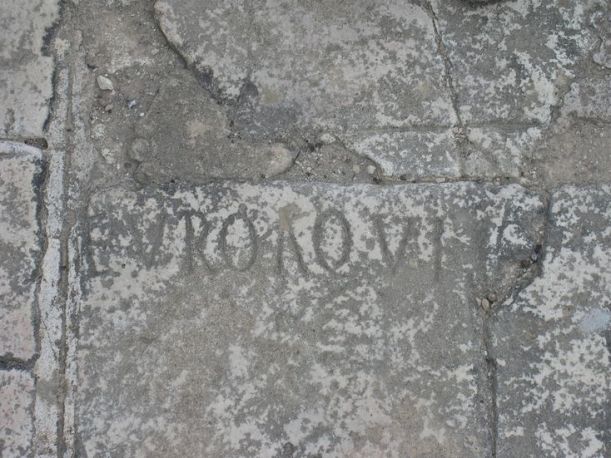

The inscription was published by A.D. Trendall in ‘Archaeology in South Italy and Sicily (1964-1966)‘, Archaeological Reports 13 (1966-1967), 39 (and fig. 17):

The retrograde inscription (LSAG) contains the name ΚΛΕΟΜΡΟΤΟΣ, ‘Mr Famous Mortal’ (the photo confirms that there was no room for β, pace the supplement in LGPN and the transcription that marks [β] as filling a damaged space: <β> would be an editorial insertion).

The giveaway that this name originated in the Thessalian dialect (of the ‘Aeolic’ ‘group’) is the sequence -ΜΡΟ-. Other dialects would have Κλεόμβροτος (as the editor and LGPN assume). That name is attested and demonstrates how all other Greek dialects eased the sequence -μρ- by the insertion (epenthesis) of β. (The same phenomenon is seen in the genitive singular ἀνδρός alongside the nominative ἀνήρ and in much later spellings of the name ‘Israel’ as Ἰστραήλ or Ἰσδραήλ and it explains why the Hebrew book named Ezra formed part of 1 Esdras in Greek versions of the Hebrew Bible.) In a compound, such as Κλεόμβροτος the sequence -μ-βρ- could be preserved between syllables, but since a word could not start μβρ-, the familiar, but poetic, βροτός ‘mortal’ arose.

That gets us as far as the -ΜΡ-. There is also the -ρο- to consider. Most Greek dialects have syllabic r reflected as -αρ- or -ρα-, but the ‘Aeolic’ ‘group’, like Latin and Arcado-Cypriot, has -ρο-: so, Attic καρδία (the same in origin as English heart), Ionic καρδίη (epic κραδίη), and Latin cor. (Aeolic is said to have had κάρζα, but it is καρδία that is transmitted in the famous poem of Sappho (31.6) that begins φαίνεταί μοι κῆνος ἰσοθέοισιν.) Cypriot is said to have had κορζία (perhaps, κόρζα). An army is a στρατός, but a στρότος for Sappho (16.1). Here, *mr-tos gives Latin mortuus ‘having died, dead’, various Lesbian-Aeolic names in -μορτος as well as μορτός known from Callimachus and Hesychius.

All that is to say that mortals should have been brats or barts in non-Aeolic and non-Arcado-Cypriot dialects and that the poetic word βροτός found in Classical Attic poetry was imported from another dialect.

It seems then that we have a Thessalian in Magna Graecia, betrayed by the phonological features of his name.

The remaining puzzle is why there is no digamma in Κλεϝόμροτος when it is plain to see in between vowels in Δεξιλάϝο, and ἀϝέθλον and at the start of ϝίσο(ν), although not after a consonant: ϝίσο-, not ϝίσϝο-). [At this point, some helpful Boeotians can be named to spell out the history of ϝισϝο- (regarded by Buck, sect. 54.d, as ‘secondary’): Ϝισϝόδικος (early seventh-century, complete with a qoppa! LSAG) gives way to Ϝισοδίκω (genitive singular: in this mid-third-century BCE inscription initial ϝ- abounds).] Since, such secondary (-)σϝ- can only be cited from (early) Arcadian, Boeotian, Cretan (the Gortyn Law ‘Code’), and Sicyonian, its absence here is not a cause for concern.

The solution is easy enough: Thessalian, the dialect of the man’s name, lost the digamma between vowels earlier than other dialects, such as that of the rest of this inscription. Buck (The Greek Dialects, pp. 48-49) could cite only fifth-century Δάϝο̄ν (DGE 563 / IG IX 2, 236), which is thought to be a Thracian name anyway, and had ἔσο̄σε (fifth-century: DGE 557 / IG IX 2, 257.10 / Buck, no. 35) as evidence for the loss of digamma between vowels and the contraction that ensued (originally: σαϝο-, as in Σαϝοκλέϝης, a Cypriot personal name). The latter inscription has ϝ|οικιάταις, unproblematically, and, curiously, κε̄υϝεργέταν (lines 3-4 and 5), but ἐποίε̄σαν (lines 5-6: cf. epigraphic (-)ποιϝεσ(-)).

Of course, all this collapses if the editor of the inscription and LGPN were right to regard the lack of a <β> as an error to be corrected. That is possible, but Κλεομρο- has the support of two other names in two early fifth-century Thessalian inscriptions, this time from Thessaly. McDevitt had earlier reported (Glotta 45 3/4 (1967): 161-163) a gent called Φιλόμροτος (attested as a genitive Φιλομρότοι, an ending peculiar to Thessalian: cf. -οι-ο in Homer) and a lady called Μροχώ (apparently followed by Ιℎερ̣[ογ]ενέ̣α̣, the patronymic adjective of Ἱερογένεις [-ης] as used in Thessalian, the rest of the Aeolic group, and in Homer…, in Αἴας Τελαμώνιος). The inscriptions are SEG XXIV 405 (text) and 406 (text).

So, we have a Greek named with Thessalian dialect phenomena, and perhaps extraction, in Italy.